By Uma Magal

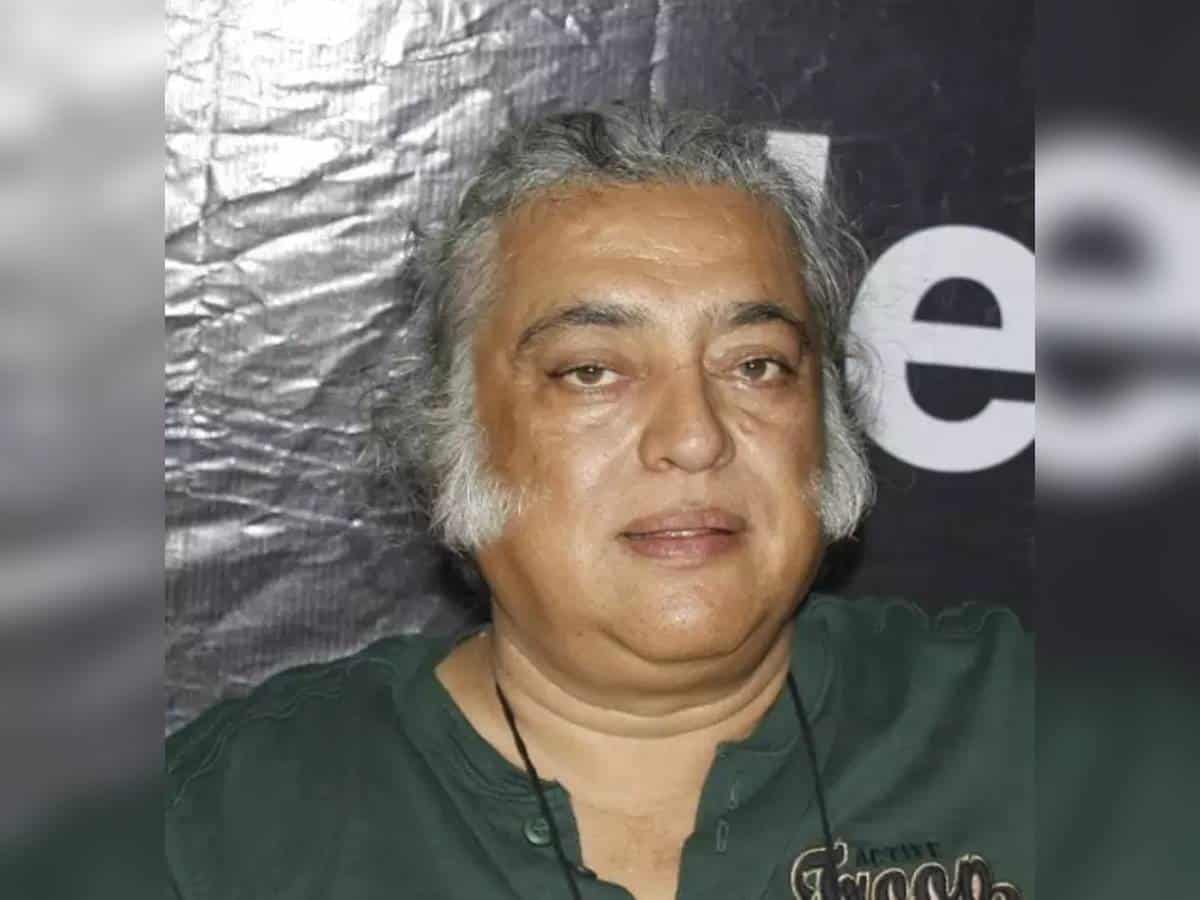

For film viewers, art direction is a much-forgotten part of filmmaking. We take it for granted when it is done well, but subconsciously sense the lack of it when done badly. Interviewing renowned art director Nitish Roy was delightful to open many types of windows into understanding the intricacy and passion behind art direction.

In Amir Khan’s Fanaa, for instance, he says: “Thewhole film was shot on a set. The shots required it to be a snow-covered scenario. I asked the producer for a truckload of salt, he said, ‘What will you do with it?’

I said, ‘Just send it to me.’ The snow was made from that salt.

In this context, he remembered with admiration Andrei Tarkovsky’s cinematic masterpiece Stalker: “It has a particularly good set, with very new snow made out of cotton.”

Deep-set memories of how other artists have worked in their films, as well as your life experiences and observations, spark the ideas and creativity to conceive great work in set design, costumes, and props. There are many facets to this that I discovered in interviewing him, but this part of this series is mainly about his work with Shyam Bengal’s films.

Awards galore

The many National and International Awards Roy has received began with the very first professional job he took on: National Award for Art Direction on Mrinal Sen’s film Kharij. Shyam Benegal visited the set, met him there, and the rest is history. Of their first meeting, he says, “My friend and I were idly spending time at Aurora Studio when the renowned filmmaker Shyam Benegal unexpectedly arrived, looking for director Mrinal Sen and the set of Kharij. During those days, the set of Kharij was discussed immensely at the then Calcutta International Film Festival. Impressed by its realism, Benegal praised the set and asked who designed it. My friend proudly introduced me. Benegal congratulated me and took my contact information. Exactly three months later, he called, offering me the role of art director for his next film, marking a turning point in my career.”

His early influences were the realistic art direction in Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen films. He spoke of Pather Panchali’s natural ambience. “Hits like Awara and Shri 420 were good films, but you can see they were shot on stage.” He loved the authentic feel of old Kolkata in Charulata; he has great admiration for the work of Sudendu Roy in Do Bigha Zameen by Bimal Roy; the work of New Wave Italian realism and neo realism. On another note, he mentions the French art director Alexander Troner’s work in Truffaut’s films: ‘It is flamboyant work. I liked the way it was so careless, carefree. We are meticulous; he would be carefree, and that gave a different feeling.”

With Shyam Benegal, Mandi was the first work engagement. Benegal showed him three location possibilities: Hyderabad, Aurangabad, and Bengaluru. Nitish Roy chose Hyderabad and spent 3 months there, making the sets in a street in Bhongir, and another one in Maula Ali. “Shyam Babu came one day before the shooting, saw it and said, ‘I think it’s too garish, please mute the colour’. I refused to mute it. Along with Qudrus Bhai, who used to help me, I took him to the Mujra area in the old city of Hyderabad. Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, and Nina Gupta came along, and we spent time there listening to songs and absorbing the atmosphere. On our return, Shyam Babu said, “Ok to my set.”

‘Bangla Bandhu’ Mujeeb

Recalling working on Benegal’s last film Mujeeb: “We recreated the whole of Bangladesh in Bombay Film City, interior and exterior. We were eating lunch during that time. I was almost 70 years old. When I met him during Mandi, I was 26. I asked him ‘At 26, how did you trust me to do a big film like Mandi?’ He said, ‘I saw your confidence’”.

Internationally, Roy has also worked on Gladiator and Isaac Asimov’s Nightfall, which is one of the most famous and influential science fiction short stories ever written. There is a most interesting connection to Hyderabad in this: Roy and his team worked out of a granite factory borrowed from a friend at Chinna Toopran in Timmapur. As he recalls: “In 1999, Gladiator had hit a crisis point. It was behind schedule; many of the sets had to be scrapped, and a lot of the budget had been eaten up already by the rejected sets. It was then that production designer Crispin Sallis was called in to help save the production. He called me. World-class sets had to be delivered to meet near-impossible deadlines but on a minuscule budget. I called the entire team of artists, sculptors, painters, and mould-makers. Those were days of no internet access, and I started working with only a hastily collected library of coffee-table books on the Roman Empire and its architecture. Working virtually round the clock, my team and I finally delivered.”

Roy has an instinct for bringing things together. In approaching the differing worlds of art cinema, parallel cinema, and full-on entertainment cinema, he spoke of how each approach reflects different priorities in terms of storytelling and audience engagement: The art direction is crucial in setting the film’s intended emotional and narrative tone and setting the stage for the audience’s experience.

Balancing act

“I’d say it’s about balancing different elements, something that’s been seen in my work and the projects I gravitate toward. Art cinema, parallel cinema, and mainstream entertainment cinema each have their distinct characteristics, but what draws me is how they can overlap or influence each other. In art cinema, you might have a slower pace or more introspective characters, while parallel cinema often deals with social issues and reflects local culture or even subversive themes. But with mainstream cinema, you also get the high-energy, larger-than-life storytelling and characters that keep people hooked. I’ve always felt that mixing the introspection and subtlety of art cinema with the appeal and reach of mainstream entertainment can make something special. You end up with a film that’s layered enough for a deeper audience but also fun and accessible to a broader crowd.”

Roy speaks insightfully about receiving the National Awards (Kharij, Mandi, Lekin, Ghayal), as well as other prestigious recognitions. He describes how they have been deeply impactful, not just as external validation, but also on the personal journey of discovering his creative potential. Every recognition gave an insight into what worked in his envisioning of the production design and setting, what was possible for him to accomplish, and gave an impetus to push the boundaries of art direction.”

In Susman, a film on Ikkat weavers, which was shot in Ikkatpalli near Hyderabad. Benegal asked him to make the setting look like El Greco’s frames. Nitish Roy went to work: “El Grecos’ frames are like colourful rainbows, pure and pristine. Unadulterated, vivacious. His foregrounds are usually cluttered with objects…” He followed that, filling the foreground with lots of thread and yarn. He also added depth between those and the background by placing different weaving objects inside the frame. “Shyam Babu was delighted! This is what keeps me going… experimenting with my work. I am ready to put salt in my tea to find out what it tastes like.” Spoken with the truly adventurous and creative drive, the film defines Roy’s best work.

Journey with Benegal

The journey with Shyam Benegal will always be remembered with deep respect and love. “Shyam Benegal was known for his detailed yet realistic storytelling, which extends deeply into his films’ art direction also. His philosophy was that the audience should feel like they are stepping into a real world rather than watching a fabricated set, which matched with my way of thinking.”

“Shyam Babu’s passing marks the end of an era in Indian cinema. His films, such as Ankur, Nishant, Manthan, Bhumika, and Mandi, were not just cinematic experiences but profound explorations of Indian society, power structures, and human resilience. Beyond films, he was a mentor, a thinker, and a relentless advocate for meaningful storytelling. It is the loss of a storyteller who made us look at our society with a critical yet empathetic lens. His films remain relevant even today, reminding us of cinema’s power to reflect, challenge, and inspire.”

With his pioneering talent in art direction, set design, feel for costumes and props, dedication to the craft, and more, Nitish Roy played a remarkable part in this brilliant legacy. It would not be wrong to say that Nitish Roy did not choose art direction; art direction chose him.